(Bug Bite Counter: 56)

Here’s your weekly video recap of what GMI has been up to: DialOasis and Ziplines!

As I sit in the sunny, temperate climate of the central valley of Santa Ana, I can only look back and smile at all that our team has accomplished in the past week in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. As I had mentioned in last week’s blog entry, we set out to the northwest region of Costa Rica (Liberia, Guanacaste) to implement DialOasis, a design project crafted by last year’s GMI cohort aiming to provide a sterile environment for locals to perform peritoneal dialysis in the comfort of their own homes. Currently, some of the patients must travel hours from their homes to attain treatment in Hospital Liberia, which consists of 3-4 procedures per day, 6 days a week, and ultimately spend their entire day (7 AM to 10 PM) away from home. As you can imagine, this not only affects their daily routine, but it impacts their families and friends as well; therefore, our goal was to create an easy-to-build structure that can fit inside the homes of these patients so they can perform these procedures themselves.

But how did we get there? Last year’s team developed the idea and plan, so that meant our job was to translate their ideas into reality.

But… in ONE WEEK?? I know. We all gawked at the idea also. I spent an entire year on my capstone project and sometimes that didn’t feel like enough time, let alone five days. In that regard, it’s only appropriate to thank the people that truly made this project feasible in the timeline that we had. Firstly, Dr. Richardson and his seemingly endless wisdom to get us everything we needed and to demonstrate that the Sprint Methodology can actually be a great learning tool. Secondly, none of this would have been possible without the people of Invenio (Roy, Ronald, Bryce, etc.) who simply just built everything that we set out to do. Additionally, thanks to the dialysis staff at Hospital Liberia who provided the space to get customer feedback. Of course, our team of 8 truly grinded this out to the end, so let’s get more into how that went down.

Given our short deadline, we decided that breaking up the team into subgroups would be the most efficient way to reach our goal. All of us wanted to jump right in and build the prototype, but 8 people with that engineering mindset would not be an efficient use of anyone’s time. So… Ryan, Tasha, and Sanjana set out to be the “build team,” or the group that would build the prototype. Anna, Callie, and Karlee were the “materials team,” which researched and scoured the city for locally-sourced materials that we could use to build our prototype. Lastly, Josh and I were the “testing team,” and our job was to ensure patient satisfaction from our device as well as develop interview guides to gather further feedback for future iterations.

Three different teams, but all integral to each other’s success. In fact, it seemed at most times during this process that there needed constant and effective communication between two or all teams to make meaningful decisions about how to proceed, as I’ll delve into in just a second. We even developed a plan the week before with goals from each team for each day, but as Dr. Richardson fully forewarned before we began, and what we soon realized, was that “plans never works, but planning does.” By understanding what each team wanted to accomplish, we could plan each day to reach those goals given our resources. It wasn’t until we truly began building our prototype did we run into all the unforeseen problems that naturally arises from the process.

If I could easily surmise my experience as part of the “testing team” this past week, it would simply be to just keep asking questions. It never ceased to amaze me how quickly we could get such important insight into a design criteria by simply asking the patient or doctor himself. We conducted a preliminary interview on Tuesday to further understand what they wanted in our design. For example,

Me: “How important is it for patients to wash their hands before they begin the procedure?”

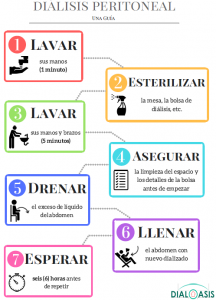

Nurse: “So important, that’s why we have so many signs teaching them how to wash their hands. They wash their hands for one minute before they sterilize their area, then they wash their hands for five minutes after. The second wash is more thorough, as it includes them washing all the way up to their elbows. The sinks you usually use are good, but they aren’t the best. In fact, there’s no need to keep a basin of water, it should just drain out. They also need to use their elbows to turn off the faucet when they are done washing to avoid any further contamination.”

Wow. We thought that question would just emphasize the hand washing procedure for the patients, but we ended up getting a whole lot more out of it. Let me explain…

- “…so many signs…” – the current signs aren’t that effective, or they aren’t conveying the required information. If they aren’t understanding hand washing signs, then they might not even be understanding the whole process, as hand washing are only the first steps. Therefore, we need to develop a better way to convey all this information, a guide of some sort.

- “…before…after…– hand washing is a two-part process. In fact, the hand washing before, we realized, was actually the less important part. This emphasized the importance of clarifying all the necessary steps in the procedure.

- “…all the way up to their elbows…no need to keep a basin of water…” – Washing all the way up to their elbows means that water runoff onto the floor is a concern as it can result in slipping. No need for a basin implies that current sinks are good, but not the most effective for the purpose of peritoneal dialysis procedures, which just needs water to drain immediately. Therefore, important design criteria regarding the size and design of the sink would need to consider these aspects to appeal to the patients.

- “…use their elbows to turn off the faucet…” – this is a concern for both the patients and the doctors, as anything touching their hands after their wash could contaminate the space and potentially harm the patient. From that, we understood that the mechanism to turn the water on and off needed to be as simple as a pushing mechanism rather than a twisting motion.

So… how important is it to ask questions? From my perspective, I say that it probably influenced most of our design. It helped us as the “testing team” to construct ways to help elaborate our ideas to patients, as you can see here…

Sometimes taking a step back to fully scope the size of the problem at hand. While it is important to begin building, without a proper understanding of what we were trying to build, we might as well have built a box like this…

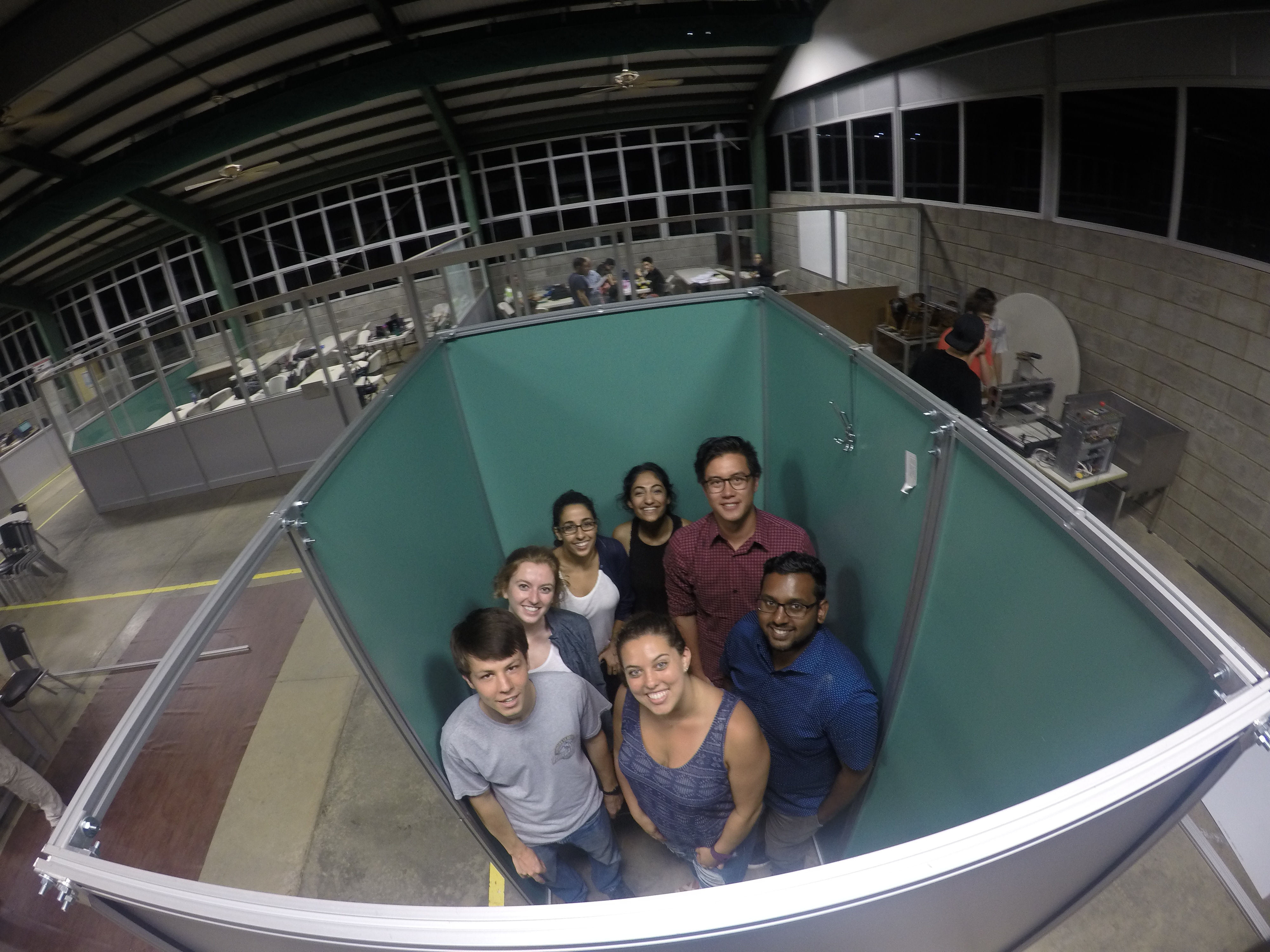

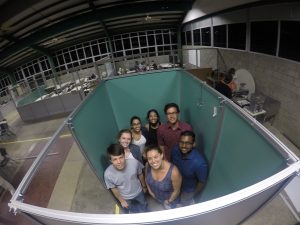

My point is that even though we were not the specific team tasked with building the structure, our input was just as valuable as any other team. Understanding what the patient wants is how products succeed. It’s easy as an engineer to build something, but if no one wants it, then was it a good design? Given our short timeline, asking direct questions was crucial to our success, and I’m glad that everyone was open minded to the task at hand. The materials team really gave us the tools that we could use (which is more limiting than our source of supplies back in the states) to build this, and that really set our limitations and expectations. The build team was the driving force. Their work brought us the finished prototype you see here…

I’m sure everyone else’s blogs will elaborate further upon their times, so I won’t go into too much detail about their work. Ultimately, this past week buzzed by, but we got a few moments to appreciate the work we had done. Patients were excited to use it. Nurses and doctors took videos and selfies next to it. Even the Director of Medicine at the hospital came down and asked to take a picture with the DialOasis team. It really made our trip out to Monteverde on our way out, where we ziplined and plunged 40 meters into free fall, all the more worth it. And now we’re in Santa Ana, as we embark on another one week short course about manufacturing processes and IP. Looking forward to sharing more, but until then, Pura Vida mis amigos.